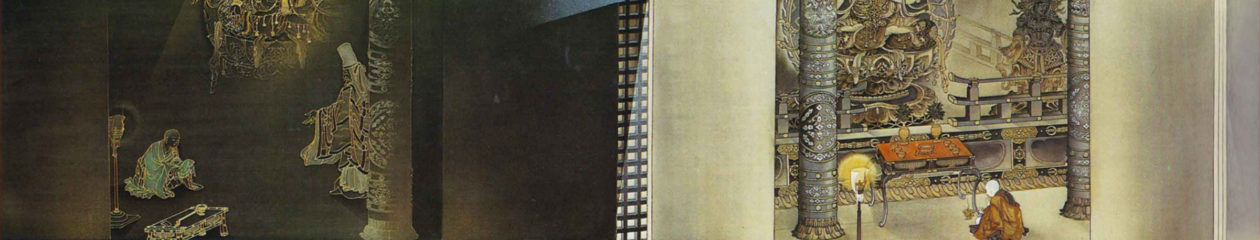

Day 20 completes Chapter 15, The Appearance of Bodhisattvas from Underground, and concludes the Fifth Volume of the Sutra of the Lotus Flower of the Wonderful Dharma.

Having last month heard Maitreya Bodhisattva and others puzzle over who are these Bodhisattva-mahāsattvas who sprang up from underground, we hear both Maitreya and the attendants of the replicas of Śākyamuni plea for an explanation.

No one will be able to count

All [these great Bodhisattvas] even if he uses

A counting wand for more kalpas

Than the number of the sands of the River Ganges.

These Bodhisattvas have

Great powers, virtues and energy.

Who expounded the Dharma to them? Who taught them?

Who qualified them to attain [perfect enlightenment]?

Under whom did they begin to aspire for enlightenment?

What teaching of the Buddha did they extol?

What sūtra did they keep and practice?

What teaching of the Buddha did they study?

These Bodhisattvas have supernatural powers

And the great power of wisdom.

The ground of this world quaked and cracked.

They sprang up from under the four quarters of this world.

World-Honored One!

I have never seen them before.

I do not know

Any of them.

They appeared suddenly from underground.

Tell me why!

Many thousands of myriads

Of millions of Bodhisattvas

In this great congregation

Also want to know this.

There must be some reason.

Possessor of Immeasurable Virtues!

World-Honored One!

Remove our doubts!

At that time the Buddhas, who had come from many thousands of billions of worlds outside [this world], were sitting cross-legged on the lion-like seats under the jeweled trees in [this world and] the neighboring worlds of the eight quarters. Those Buddhas were the replicas of Śākyamuni Buddha. The attendant of each of those Buddhas saw that many Bodhisattvas had sprung up from under the four quarters of the [Sahā-World which was composed of one thousand million Sumeru-worlds and stayed in the sky. He said to the Buddha whom he was accompanying, “World-Honored One! Where did these innumerable, asaṃkhya Bodhisattvas come from?”

That Buddha said to his attendant:

“Good Man! Wait for a while! There is a Bodhisattva

mahāsattva called Maitreya [in this congregation]. Śākyamuni

Buddha assured him of his future attainment of Buddhahood,

saying, ‘You will become a Buddha immediately after me.’

Maitreya has already asked [Śākyamuni Buddha] about this

matter. [Śākyamuni] Buddha will answer him. You will be able

to hear his answer.”

The Daily Dharma from March 15, 2018, offers this:

Good Man! Wait for a while! There is a Bodhisattva-mahāsattva called Maitreya [in this congregation]. Śākyamuni Buddha assured him of his future attainment of Buddhahood, saying, ‘You will become a Buddha immediately after me.’ Maitreya has already asked [Śākyamuni Buddha] about this matter. [Śākyamuni] Buddha will answer him. You will be able to hear his answer.

This passage from Chapter Fifteen of the Lotus Sūtra is the answer one of the Buddhas of the replicas of Śākyamuni Buddha gives to his attendant. In the story, innumerable Bodhisattvas have come up through the ground of this world of conflict after the Buddha asked who would continue his teaching after his extinction. Neither the attendant, nor anyone gathered to hear the Buddha teach had seen those Bodhisattvas before and wanted to know where they came from. Our practice of the Wonderful Dharma does not mean merely accepting what we do not understand. We need to raise questions when they occur. These questions show that we are capable of greater understanding. They lead us even closer to the Buddha’s wisdom.

The Daily Dharma is produced by the Lexington Nichiren Buddhist Community. To subscribe to the daily emails, visit zenzaizenzai.com