In 1959 Walpola Sri Rahula published a concise summary of the teachings of the Buddha. The Rev. Dr. Rahula, 1907-1997, was a trained Buddhist monk in Sri Lanka. As explained by Paul Demieville in the Foreword:

In 1959 Walpola Sri Rahula published a concise summary of the teachings of the Buddha. The Rev. Dr. Rahula, 1907-1997, was a trained Buddhist monk in Sri Lanka. As explained by Paul Demieville in the Foreword:

The book … is a luminous account, within reach of everybody, of the fundamental principles of the Buddhist doctrine, as they are found in the most ancient texts, which are called ‘The Tradition’ (Āgama) in Sanskrit and “The Canonic Corpus’ (Nikāya) in Pali.

As Rahula explains in his Preface:

I have tried in this little book to address myself first of all to the educated and intelligent general reader, uninstructed in the subject who would like to know what the Buddha actually taught. For his benefit I have aimed at giving briefly, and as directly and simply as possible, a faithful and accurate account of the actual words used by the Buddha as they are to be found in the original Pali texts of the Tripiṭaka, universally accepted by the scholars as the earliest extant records of the teachings of the Buddha.

In 1974 a second edition was published which added a number of selected sutras.

Personally, as a follower of Nichiren, I have read this book from the perspective of the teachings of the Lotus Sutra. I have set aside a number of quotes from the book which I will be publishing daily through June 12. I’ve selected these quotes as explanations of the foundational teachings of the Buddha.

However, some of what Rahula teaches is problematic for me as a devotee of Japanese Buddhism. In addressing the Buddha’s spirit of tolerance, Rahula writes:

What the Buddha Taught, p4-5In the third century B.C., the great Buddhist Emperor Asoka of India, following this noble example of tolerance and understanding, honored and supported all other religions in his vast empire. In one of his Edicts carved on rock, the original of which one may read even today, the Emperor declared:

‘One should not honor only one’s own religion and condemn the religions of others, but one should honor others’ religions for this or that reason. So doing, one helps one’s own religion to grow and renders service to the religions of others too. In acting otherwise one digs the grave of one’s own religion and also does harm to other religions. Whosoever honors his own religion and condemns other religions, does so indeed through devotion to his own religion, thinking “I will glorify my own religion.” But on the contrary, in so doing he injures his own religion more gravely. So concord is good: Let all listen, and be willing to listen to the doctrines professed by others.

We should add here that this spirit of sympathetic understanding should be applied today not only in the matter of religious doctrine, but elsewhere as well.

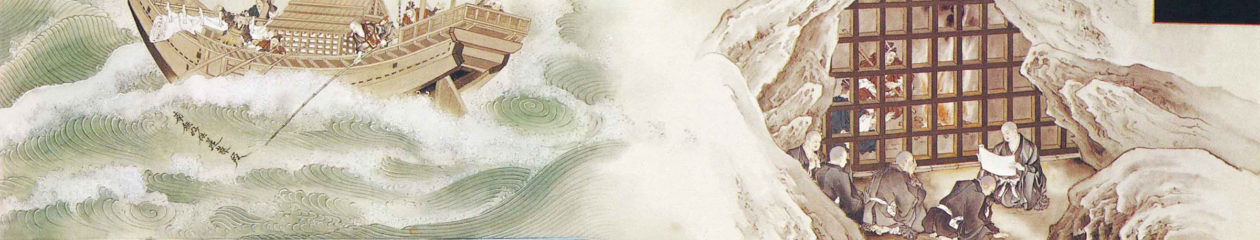

This spirit of tolerance and understanding has been from the beginning one of the most cherished ideals of Buddhist culture and civilization. That is why there is not a single example of persecution or the shedding of a drop of blood in converting people to Buddhism, or in its propagation during its long history of 2500 years. It spread peacefully all over the continent of Asia, having more than 500 million adherents today. Violence in any form, under any pretext whatsoever, is absolutely against the teaching of the Buddha.

It may be true that “Violence in any form, under any pretext whatsoever, is absolutely against the teaching of the Buddha,” but that was not the experience in Japan. As the History of Japanese Religion by Masaharu Anesaki points out, the Tendai soldier monks of Mount Hiei felt compelled to pick up arms and battle Nichiren’s followers.

History of Japanese ReligionThe last and bitterest of the combats was fought in Miyako in 1536, when the soldier-monks of Hiei in alliance with the Ikkō fanatics attacked the Nichirenites and burnt down twenty-one of their great temples in the capital and drove them out of the city. Shouts of “Namu Myōhō Renge Kyō,” the slogan of the Nichirenites, vied with “Namu Amida Butsu,” the prayer of the Ikkō men; many died on either side, each believing that the fight was fought for the glory of Buddha and that death secured his birth in paradise.

Again, as a follower of Nichiren and the Lotus Sutra, I stumble when I encounter discussions of “Truth.”

Early in the book The Rev. Dr. Rahula addresses this topic:

What the Buddha Taught, p5The question has often been asked: Is Buddhism a religion or a philosophy? It does not matter what you call it. Buddhism remains what it is whatever label you may put on it. The label is immaterial. Even the label ‘Buddhism,’ which we give to the teaching of the Buddha, is of little importance. The name one gives it is inessential.

What’s in a name?

That which we call a rose,

By any other name would smell as sweet.In the same way Truth needs no label: it is neither Buddhist, Christian, Hindu nor Moslem. It is not the monopoly of anybody. Sectarian labels are a hindrance to the independent understanding of Truth, and they produce harmful prejudices in men’s minds.

A few pages later The Rev. Dr. Rahula underscores this with the words of the Buddha:

What the Buddha Taught, p10-11Asked by the young Brahmin to explain the idea of maintaining or protecting truth, the Buddha said: ‘A man has a faith. If he says “This is my faith,” so far he maintains truth. But by that he cannot proceed to the absolute conclusion: “This alone is Truth, and everything else is false.” In other words, a man may believe what he likes, and he may say ‘I believe this.’ So far he respects truth. But because of his belief or faith, he should not say that what he believes is alone the Truth, and everything else is false.

The Buddha says: ‘To be attached to one thing (to a certain view) and to look down upon other things (views) as inferior — this the wise men call a ‘fetter.’

Is it a “fetter” to hold that the Lotus Sutra is the supreme teaching of the Buddha, that it encompasses and embraces all of the provisional lessons taught before it?

I will leave it at “This is my faith.”