Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 36-37In the proper ritual of the Nichiren Sect, as performed by the believer in his home or in the temple, the invocation of the Title and the contemplation of the Mandala are always combined. The two actions supplement each other. Their homogeneousness has been made perfectly clear by the Nichiren scholar Gyōkei Umada, in the words:

When a man gazes at the and recites the Sacred Title, heart and soul, subjectivity and objectivity become fused into one whole, and the worshipper realizes in himself the excellent qualities of the Supreme Being, and thereby his short life is made eternal and his limited virtue infinite. In short, Śākyamuni, the Scripture of the Lotus of the Perfect Truth, and the worshipper, become united, in perfect accord, and herein lies the consummation of the creed of the Nichiren Sect: the peace of mind of believers and religious life. The result of all this is the realization of the Buddha Land in the present state of existence.

To Nichiren, uttering the Title reverently and earnestly was tantamount to practicing austerities and doing good, in so far as salvation in the Nichiren-fold is reached by Self-Power (ji riki). However, according to Nichiren’s view, the devotee simultaneously “takes shelter under the wings of Śākyamuni’s compassion, which endeavors to redeem all beings in the Age of Decadence, when uniquity would abound and the love of many would wax cold.” This of course implies salvation by the Other Power (ta riki.) Therefore we find in the dogmatics of Nichiren and his School a union of the Power of the Buddha with the Power of Devotion.

Category Archives: Petzold Nichiren

Salvation by Faith and Invocation

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 35-36In the Hokke daimoku-shō, Nichiren explains that the invocation of the Title saves the sinner from perdition. He maintains that “without knowledge of the meaning of the Lotus, without understanding of morality, a man can avoid sins, escape the Four Evil Destinations and attain perfection by the mere utterance once a day, once a month, once a year, or even once in a lifetime of the seven syllables Na-Mu-Myō-Hō-Ren-Ge-Kyō.” We see here psychologically, the nearest approach imaginable to Hōnen Shōnin’s standpoint, which Nichiren attacked so vehemently. Both cases deal with salvation by faith and invocation. Though both founders state that even a single invocation in a lifetime is sufficient, in practice the invocation in both the Nichiren and Jōdo sects continues for hours. In the Nichiren Sect a drum is beaten, in the Jōdo sect a conch-shaped wooden battling-block—both used to assure the proper rhythmical cadence of the invocation, and to concentrate the attention of the devotee and transport him into a state of ecstasy.

This psychological element is obvious from an observation of any Nichiren practice—devotees in their homes or temples, a procession or a ceremony. An example might be the grand memorial ceremony, oeshiki, celebrated at Ikegami near Tokyo on the twelfth and thirteenth of October. Day and night processions of believers chant the Sacred Title, beat drums, play fifes, ring bells and flourish their mandō (richly decorated paper lanterns typical of the Nichiren Sect). Further, while adherents of Hinayāna and ancient Mahāyāna Schools refute any association of hypnotism with their meditation, Nichiren scholars state openly that their meditation is impregnated with it. In his Japanese Civilization, [Kishio] Satomi determines five reasons for uttering the Sacred Title: self-intuition or reflection, expression of ecstasy, stimulation of continuous expression, autohypnotism for inspiration, and manifestation of one’s standard.

The Practice of the Original Buddha

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 34-35Nichiren is often compared to the Bodhisattva Sadāparibhūta, known in Japan as Jōfugyō Bosatsu i.e., the Bodhisattva Never Despise. Living in a time when the spiritual capacity of the people was at its lowest ebb, the Bodhisattva did neither read nor recite, expound nor copy the sutra, but merely honored and respected the Buddha-seed existing in all living beings. The Jōfugyō Bosatsu Chapter of the Hokekyō tells his story:

That monk did not devote himself to reading and reciting the Sūtras, but only to paying respect, so that when he saw afar off a member of the four classes of disciples, he would specially go and pay respect to them, commending them, saying: “I dare not slight you, because you are all to become Buddhas”. Amongst the four classes, there were those who, irritated and angry and low-minded, reviled and abused him saying: “Where does this ignorant bhikshu come from, who takes it on himself to say, “I do not slight you”, and who predicts us as destined to become Buddhas? We need no such false predictions.” Thus, he passed many years, constantly reviled but never irritated or angry, always saying: “You are to become Buddhas”. Whenever he spoke thus, they beat him with clubs, sticks, potsherds, or stones. But, while escaping to a distance, he still cried aloud: “I dare not slight you. You are all to become Buddhas”. And because he always spoke thus, the haughty monks, nuns, and their disciples dubbed him: Never Despise.

Nichiren, however, did not recognize the comparison, since he maintained that the practice of “receiving and keeping” was to be understood as the practice of the Original Buddha. Recitation of the Title by men was thus the voice of the Original Buddha; all men could realize the Buddha in themselves by reciting the Title.

The Practice of Honge Bosatsu

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 33-34[The Nichiren-shū kōyō (Manual of the Nichiren Sect published in 1928) written by Nichiren scholar Shimizu Ryōzan] explains Daimoku in the following way: “The Daimoku is the practice of Namu Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō. It is the manifestation of the believing mind by sowing the seed and is called Juji no ichigyō or ‘The one practice of receiving and keeping’—the terms ‘receiving’ and ‘keeping’ being synonymous with believing.”

A distinction to be made in text authority justifies Nichiren’s concept of Kanjin. In the Shakumon part of the Hoke-kyō, the “Fivefold Practice” is taught as the practice of the Shakke Bosatsu [Bodhisattvas who are followers of a provisional Buddha]. This practice consists of:

- juji—receiving and keeping, i.e. believing

- doku—reading

- ju—reciting from memory

- gesetsu —expounding

- shosha—copying

However, the Hommon part of the Hoke-kyō especially recommends the one practice of “receiving and keeping,” saying it is the practice of Honge Bosatsu [Bodhisattvas taught by the Eternal Śākyamuni]. Thus, basing himself on the Hommon point of view, Nichiren can say with Honge Bosatsu that there ought to be no other practice but the manifestation of belief, “sowing the seed,” by uttering the Title. Though this view seems very narrow, we are assured that it is rather very deep, since in the one practice of “receiving and keeping” all practices of all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas are summarized. Since the one practice of ju ji is all-comprehensive, it assimilates the other four practices.

A point to remember is that before his exile to Sado, Nichiren adhered to the fivefold practice; though determining ju ji to be the proper practice, he recognized the four other ones as helping practices. It was during his stay in Sado that he adopted exclusively the one practice of ju ji.

Practical Meditation and Practical Devotion

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 33An original statement of Nichiren’s conception of the Sacred Title is contained in his Kanjin-honzonshō. Telling us that the invocation of the title is to be considered as Kanjin, or “Meditation,” he states the difference between Tendai meditation and Nichiren meditation: The Tendai Meditation “possesses completely in one thought the three thousand from the point of view of reason,” while the Nichiren Meditation “possesses completely in one thought the three thousand from the point of view of matter.” The “three thousand,” as we know, means all psychical and physical phenomena or the whole universe understood as a mental as well as a physical entity. “From the point of view of reason” means “in theoretical respect” or “in abstract”; “from the point of view of matter” means “in practical respect” or “in concrete.”

The Tendai meditation if further explained as always a meditation on some objective truth, for instance on the truth of “non-form being the real form” (mu sō jissō), or on the “three truths” (san tat) of “the Empty, the Phenomenal Reality, and the Middle” (kū, ke, chū), which are the objects of the “three meditations” (san gan). On the contrary, the method used by the Nichiren Sect, in which the devotee recites the title and turns his face to the Daimandara is characterized by Nichiren as “practical meditation and practical devotion in which faith takes the place of wisdom” (i-shin dai-e no ji-kan ji-gyō). Consequently what is called kanjin or “meditation-mind” by Nichiren is not to be understood as meditation in any ordinary meaning, but as shinjin or “believing mind.” In the Nichiren School we have therefore to deal not with “meditation,” but with “belief.” Kanjin does not imply here knowledge by introspection as the Tendai meaning does but understanding by belief. In short, the Tendai School meditates on some objective truth and does not use the method of reciting the Title, which in the Nichiren Sect holds such a prominent place.

The Whole Life-Process Within the Ten States of Existence

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 31-33[T]he Title or Daimoku is the five or seven characters which make up the full name of the Hoke-kyō. The title of the Sūtra, says Nichiren doctrine, is the essence of the whole sūtra, the holy teaching of the Buddha’s life, the principle of all things, and the truth of eternity; the fullest implications of the title are inexplicable and inconceivable, understood not even by subordinate Buddhas. The title of the original doctrine is to be believed in, not understood.

Tendai Daishi had already considered that the title of the Hoke-kyō included the essence of the whole sutra, but this was in accordance with the general view that the titles of the holy texts proclaimed by Buddha contained, in a condensed and abbreviated way, the full text. It was Tendai Daishi who used the “five profound meanings” (gojū gengo to explain the sūtras, a system which we remember as containing:

l. myō—the name

2. tai—the substance

3. shū—the principle

4. yū—the action

5. kyō—the teachingThe first concerns the title of the sūtra; the second its philosophical essence, the third its practical import; the fourth its efficiency or the effect gained by it; the fifth the respective rank which the particular sūtra, on account of its doctrine holds among all sūtras.

Tendai Daishi found a justification for his method in Chapter XXI of the Hoke-kyō, which says:

In fact, all the truths possessed by the Tathāgata, all the sovereign, divine powers of the Tathāgata, all the stocks of mysteries of the Tathāgata, all the profound things of the Tathāgata are proclaimed, displayed, revealed, and expounded in this Sūtra.

Basing himself on this passage, he interpreted the truths possessed by the Tathāgata as the title of the Hoke-kyō and that all the sovereign, divine powers of the Tathāgata corresponded to its “essence”; that all the stocks of mysteries of the Tathāgata were to be understood as its “principle”; that all the profound things of the Tathāgata signified its “action”; and that the revelation and promulgation coincided with its “teaching.”

Nichiren merely adopted Tendai Daishi’s method in dealing with the Hoke-kyō. His identification of the term myō (wonderful) with death, of hō (dharma) with birth, and the equalization of these two with renge (lotus) conforms to Tendai Daishi’s view in which the title involves the whole life-process within the ten states of existence.

The Secret Name of Mahāvairocana

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 30-31[In his Nichiren-shū kōyō (Manual of the Nichiren Sect), Nichiren scholar Shimizu Ryōzan] characterizes Myō hō ren ge kyō as not the name of the sutra, but the secret name of Mahāvairocana1, the Omnipresent Buddha; not the substance of the reason of all dharmas, but the secret substance of Mahāvairocana; not the principle of the cause and effect of the One Vehicle, but the secret principle of Mahāvairocana; not the action that creates belief by destroying all doubt, but the secret action of Mahāvairocana; not the teaching of the twenty-eight chapters, but the secret teaching of Mahāvairocana. Further, Shimizu states that though Honzon is one of the three objects of Kanjin (i.e., where Kanjin is the wisdom of the believer, Honzon is the object of belief; where Kanjin is the practice, Honzon is the enlightenment), such a method of distinguishing between the two does not express the final concept of the Nichiren School. In ultimate meaning the School considers Kanjin identical with Honzon, Honzon identical with Kanjin. Thus, he claims, there is really no difference between practice and enlightenment, since all cause and effect, the self and others are the secret Oneness of Mahāvairocana.

Perhaps a final comment will clarify what Shimizu is saying. The full title of the Hoke-kyō used in recitation is, as we know, Namu Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō. Namu, broadly a term of adoration, is written in two characters, and Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō, the proper title of the sutra, is written in five characters. When we consider the two characters of Namu in their reference to the five characters of Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō the reciprocal relation between Kanjin and Honzon becomes clear. The two characters are the wisdom of the believer, the five characters the object of belief. The two characters are the practice, the five characters are the enlightenment. Thus we have the Honzon of Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō existing in the Tathāgata; and the Kanjin of Namu belonging to the practices. However, as we are repeatedly assured, there is no difference between object and subject, practice and enlightenment, self and others, since all are identical with Mahāvairocana. Consequently there is no real distinction between the Tathāgata and the practices, the two being unified in Namu Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō. The Namu of the practitioner is identical with the Namu of the Tathāgata, the Tathāgata’s practice, and with his enlightenment without beginning. The two characters of Namu mean the absolute Oneness of object and subject, of self and others, of the practitioner and the Tathāgata. Thus the five characters are identical with the seven characters of Namu Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō; these seven characters are identical with the two characters of Namu; these two characters are identical with the “one momentary mind” of the believer; and this “one momentary mind” is identical with the whole substance of Mahāvairocana.

- 1

- Mahāvairocana is the Eternal Śākyamuni. The Sutra of Contemplation of Universal Sage, the concluding sutra in the threefold Lotus Sutra, contains this:

The ethereal voice will then immediately reply, saying: “Śākyamuni Buddha is Vairocana – the One Who Is Present in All Places.

‘The Origination of the Fundamental Buddha’

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 28A view of the universe based on the idea of this Original Buddha has been formulated by Nichiren scholars. The doctrine, “The Origination of the Fundamental Buddha” (hom butsu engi), is based on the Hommon part of the Hoke-kyō and maintains that the Original Buddha dwells eternally in the three periods of past, present and future; that he is identical with the three bodies (Dharmakāya, Sambhogakāya, and Nirmāṇakāya). He educates all living beings in the nine worlds and three periods, making them dwell peacefully by teaching the three benefits of sowing the seed, bringing it to ripeness and letting it reach deliverance. This Original Buddha shows his birth in non-birth, his death in non-death; since the existence of the universe depends on his virtue and mercy, it cannot exist separate from him.

Consequently, the Great Mandala represents both the kingdom of the Original Buddha and the universe that originates from the Original Buddha. Also, since all living beings are the nine worlds that originate from the Original Buddha, a belief in this fact unifies the believer with the substance of the Original Buddha.

The Mandala-Cult

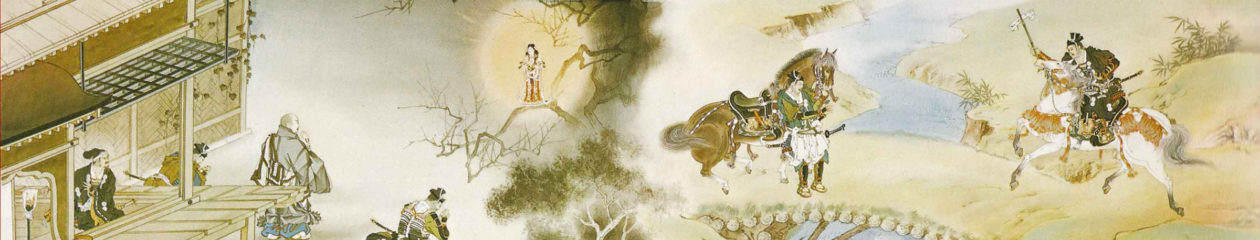

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 27-28The Mandala-cult was by no means an innovation brought about by Nichiren and his sect. The Japanese Tendai and Shingon Schools knew and worshipped two fundamental Mandalas, four different styles of Mandalas, and an almost limitless number of special Mandalas. What was new was the special kind of Mandala composed by Nichiren, and the interpretation of the Ultimate Reality connected with it. The Nichiren-Mandala is far from being a work of art. Of the utmost simplicity, it shows no figures or symbolized instruments or flowers; but instead mere names in black ink which are, as a rule, all written in Chinese characters. (Sanskrit letters are used only exceptionally and very sparingly; for example, in indicating the names of Fudō and Aizen, the guardian spirits of Buddhism.) The whole is made very roughly, without linear arrangement or color. The charm it exercises is purely spiritual. There is nothing in this abstract representation that could divert the mind of the devotee from concentrating on the Supreme Being. We cannot therefore be greatly surprised over the statement made by fervent Nichiren-believers, that the perfectly graphical method of symbolizing the Supreme Being or the Holy Universe as used by Nichiren in his Mandala is much more effective than the original Buddha’s image or Buddha’s picture or an abstract heaven. The act of religious worship of this Mandala, as Anesaki puts it, unites on the one hand the adoration of the universal Truth embodied in the person of Buddha, and on the other hand the realization, in thought and life, of the Buddha-nature in ourselves.

All Beings in the Ten Existences Attain Buddhahood

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 23In Chapter XVI of the Hokekyō on the “Duration of the Tathāgata’s Life,” Śākyamuni himself says that he is this Original Buddha; but not only was Śākyamuni so, but ourselves also; and the ten regions or states of existence, from the regions of the Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, Pratyekabuddhas and Śrāvakas down to those of the Devas, Human Beings, Asuras, Beasts, Pretas and Dwellers in Hell are all transformations of the Original Buddha. Nichiren represents this Buddha through the Honzon or chief object of worship in his Great Mandala. In the center of the Mandala the five characters Myō Hō Ren Ge Kyō (the title of the Hokekyō) are written, and around it the names of the Ten Worlds, which show the nature of the Original Buddha. By virtue of the all-enlightening power of the Title, each of the Ten Worlds is supposed to reveal its original sanctity, its intrinsic merit, and consequently all beings represented in the Ten Existences attain Buddhahood.