This is another in a series of daily articles concerning Kishio Satomi's book, "Japanese Civilization; Its Significance and Realization; Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles," which details the foundations of Chigaku Tanaka's interpretation of Nichiren Buddhism and Japan's role in the early 20th century.

Kishio Satomi holds that Nichiren, a Tendai priest by training, launched his crusade as an effort to restore Dengyo’s Tendai teaching of the importance of the Hokekyo – the Lotus Sutra.

Nichirenism and the Japanese National Principles, p123-126Through his long and thorough researches he at last arrived at his climax, viz. that the Hokekyo was the sole ultimate adoration for the people. The Great Master Dengyo, the founder of Hiei, was the right master of the Hokekyo, none the less his successors took the wrong way at that time, or I should say, the Great Masters Jikaku and Chisho, who were Dengyo’s disciples, adopted Shingon-secularism, which they mixed with the doctrine of the Hokekyo. They proclaimed that the theories of the Hokekyo and Shingon-mysticism were quite one and the same, but that the latter was superior to the former in a practical sense. Nichiren saw the greatest fallacy therein, and denounced these two masters’ views to the public when an academical council was held in Hiei. …

Thus it is clearly evident [to Nichiren] that at that time the school of Dengyo very much deviated from Dengyo’s right view. This fact once disappointed [Nichiren] when he saw the light, but he immediately resolved to resuscitate the right teaching of Dengyo and begin the movement of the Hokekyo. He visited Dengyo’s grave on the hill and mourned over his soul, at the loss of his right teaching. Nichiren left Hiei for his native village, where his parents and his old master were still alive awaiting their loving boy and disciple.

Now, [Nichiren] feels it incumbent upon him to say something about his learning, and from the conclusion he had drawn it must be most faithful and strong advice which, though it might sound harsh to the people’s ears, must be uttered. It is also written in the Hokekyo, that in consequence of those who will propagate the Law in the beginning of the Latter Law against all the sects and all people, many dreadful persecutions shall threaten him. And Nichiren knew it too clearly; but he was a man. He fell into mental agony concerning “to be persecuted” or “not to be persecuted.” He thought and thought night and day, and at last resolved on denouncement, while all the neighbors welcomed him, expecting to hear graceful sermons about the Amita Buddhism.

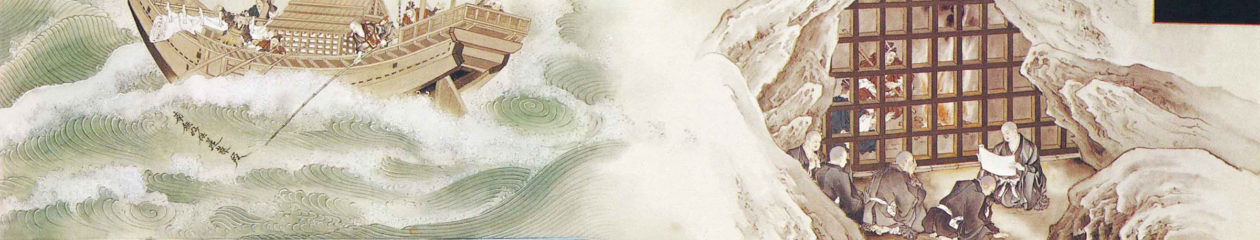

Nichiren retired for a week to a quiet room in the forest, near the monastery of Kiyosumi. As soon as he had prepared himself there Nichiren left the forest house at dawn and climbed the summit of the hill which commands the vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

Motionless he stood looking Eastward; a loud voice broke forth from his lips, saying, “Namu Myōhōrengekyō, Adoration to the Perfect Truth of the Lotus!” When the golden disc of the sun began to break, it was to heaven and earth that Nichiren’s proclamation of his new religion was made, calling the all-illuminating sun to witness. This happened at dawn of the 28th day of April 1253.

After this proclamation to the universe, he got his new name of Nichiren, which means “Sun-Lotus,” suggested by the Hokekyo (see Works, pp. 609, 1054, 845). Nichiren began to descend the hill in an extreme ecstasy and came back among the people. At noon of the same day he preached for the first time his unique religion based on the Hokekyo, in a service room facing south, Alas! quite contrary to the hearers’ expectation, Nichiren denounced all the wrong Buddhism in the presence of his parents and friends, his old master and the neighbors. Thereupon their prodigious astonishment turned into persecution. Nichiren was banished forever from his old master’s monastery, while only his parents among all who heard him were believers.

He thought, at this time, of one of the stanzas of “Exertion” in the Hokekyo. It runs:

“One will have to bear frowning looks, repeated disavowal (or concealment), expulsion from the monasteries, many and manifold abuses ” (Kern, p. 261 ; Yamakawa, p. 392).

This idea that Nichiren wanted to restore Dengyo’s teaching was directly disputed in Bruno Petzold’s book, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren–A Lotus In The Sun, in which he examined Nichiren’s doctrine from the Tendai perspective.

Petzold wrote:

A point of interest here is the leniency Nichiren displays in dealing with Dengyō Daishi, in view of the fact that Tendai Daishi’s doctrine was so altered in its transplantation to Japan. Dengyō added the Shingon teaching, giving the impetus to the further development of his school in the direction of mikkyō or secret teaching. He added Dharma Daishi’s Zen and Endon Kai transmission to proper Tendai, and gave to Hieizan a generous hospitality to the Amida Belief. These actions displayed his wish to make his Tendai Sect a synthesis of all strains of the One Vehicle Teaching. To this harmonizing tendency, that enlarged more and more the circle of the One Vehicle and showed the most conciliatory spirit to varied teaching, was opposed Nichiren’s tendency of narrowing the One Vehicle to exclude anything that was not harmonious with his “practical” and original doctrine. Of course, a harmonizing tendency had already dominated the pure Hokke En teaching of Tendai Daishi, since he used other sūtras and śāstras as well as the Hoke-kyō. Nichiren bases himself solely on the Hoke-kyō, and still his tolerance of these two Tendai teachers did not break. Therefore, it would be wrong to state that Nichiren’s intention was to purge Dengyō Daishi’s teaching of all “later additions,” or to restore Tendai Daishi’s doctrine to its pristine purity. Neither of these could have been Nichiren’s aim. Since he considered himself as having a much deeper comprehension of the Hoke-kyō than these two founders, and since the time had arrived for propagating this new view, he resolved to devote himself entirely to this mission alone. Certainly he respected Tendai Daishi and Dengyō Daishi as the originators of the Hokke teaching, but he never meant to acquiesce to their doctrine. He charged himself instead with the propagation of the supreme truth of the Hoke-kyō, a truth that had not been anticipated by his two predecessors.

Petzold, Buddhist Prophet Nichiren , p 109

Table of ContentsNext