This is another in a series of articles discussing the book, Nichijo: The Testimony of John Provoo.

Sometime in 1936 John Provoo’s search for someone who could teach him about the Lotus Sutra led him to Bishop Ishida Nitten, who helped found the Nichiren Hokke Buddhist Church at 2016 Pine Street in San Francisco.

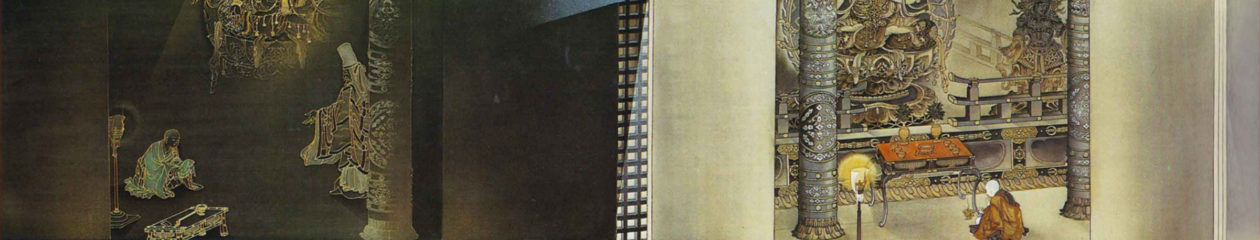

Nichijo: The Testimony of John Provoo, p28Bishop Ishida spoke very little English, and in the style typical of teacher-student relations in the East, he would put me off, saying, “Go away,” or “I am much too busy,” or “Come back another time.” A prospective disciple is tested and prepared in this way. I kept going back. Finally the Bishop gave me a collection of letters that he had laboriously translated from the Chinese into English. I had been accepted and instruction had begun, but slowly.

But Provoo had the good fortune to find another Nichiren teacher.

A traditional saying in the East is “when the disciple is ready, the master will appear.” I came across another smaller temple in a two-story house with the garage underneath made into an orthodox Nichiren temple. The priest was a cheerful round-faced man with glasses named Aoiyagi Shoho, who later became Bishop Nippo. He was from a priestly family whose ancestral home is at Ichinose, not far from one of the major temples of the Nichiren sect. This time my reception was entirely different. On my first visit the priest welcomed me warmly. “Please come, come in,” which was practically the extent of his English. It was a relationship that seemed to be fully developed at the first meeting, although neither of us could speak the other’s language, and the relationship would last with the same strength for our lifetimes. We taught each other our respective languages, and night after night we studied the Lotus Sutra, often until after midnight. My understanding of this highest teaching was intertwined with the learning of the Japanese language and most of the realizations came to me without first being translated into English. I had quickly reached the stage where I could think in Japanese. I could think and express my deepest thoughts in Japanese. At times I felt that East and West were unified within me, but in the external world events were pulling East and West apart. The Lotus seemed the only thing that resolved all contradictions. I memorized the 16th chapter in Japanese, and often chanted it from that day forward. In it, Buddha says to his audience:

Beneath the dark surface of this crumbling illusion,

My perfect world shimmers with light.

Though this illusion seems burning,

And these suffering beings lie broken and bleeding,

My perfect world is here,

And these beings are whole and filled with light.

I have revealed the fate of the world:

That all beings shall be illumined.”

Nichijo: The Testimony of John Provoo, p28-30

At this point I need to renege on my promise to set aside my journalist’s skepticism.

I’m puzzled by Provoo’s quote from the gāthās of Chapter 16. There are verses similar, for example Senchu Murano’s translation offers:

The [perverted] people think:

“This world is in a great fire.

The end of the kalpa [of destruction] is coming.”

In reality this world of mine is peaceful.

It is filled with gods and men.

The gardens, forests and stately buildings

Are adorned with various treasures;

The jeweled trees have many flowers and fruits;

The living beings are enjoying themselves;

And the gods are beating heavenly drums,

Making various kinds of music,

And raining mandārava-flowers on the great multitude and me.[This] pure world of mine is indestructible.

But the [perverted] people think:

“It is full of sorrow, fear, and other sufferings.

It will soon burn away.”Because of their evil karmas,

These sinful people will not be able

To hear even the names of the Three Treasures

During asaṃkhya kalpas.

None of the English translations of the Lotus Sutra has verses similar to those Provoo offers referencing the light of the Buddha in Chapter 16. Is this because he is translating the Japanese into English rather than translating Kumārajīva’s fifth-century Chinese translation into English? I like the sentiment expressed in Provoo’s verses, but I’m too much of a literalist to allow this discrepancy to stand without comment.