His pugnacious spirit and his tender heart

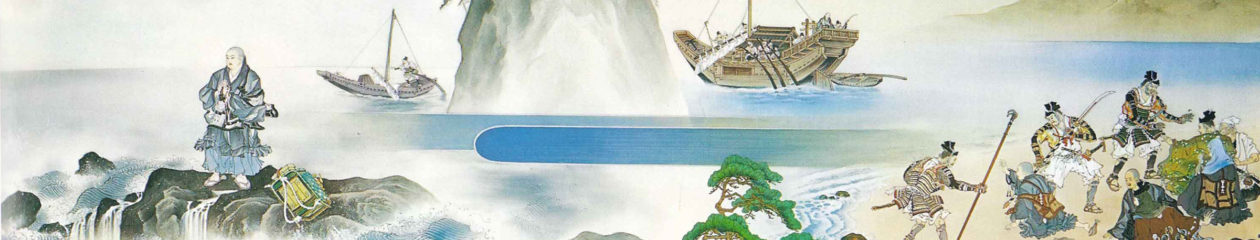

It was in the second month of 1263, that Nichiren was released from his banishment in Izu. The reason for the release is unknown, but his return was a triumph for Nichiren. By the rising of the mob, and during his exile, his abode had been devastated, his disciples ill-treated, and some of his lay followers threatened with confiscation of their properties. Yet they remained faithful to the prophet and his instructions; and when the master came back to Kamakura, they flocked to him, and welcomed him with tears of joy. It seems that some of them wished to see their master mitigate his trenchant attacks upon other Buddhists, believing that the true religion could be propagated without antagonizing others. This is reflected in Nichiren’s strong insistence, in an essay written immediately after his return, on the proposition that an exclusive devotion to the unique truth of the Lotus is the necessary condition to salvation. It was impossible for him to modify his attitude, for he was a man who had passed through perils and was thereby strengthened in the conviction of his own mission and destiny. He now preached in a manner more intransigent than before and drew a strong contrast and a sharp line of demarcation between his gospel and Amita-Buddhism as well as Shingon mysticism. The forcible arguments and vehement invectives, directed especially against these two schools, exhibit the method of Nichiren’s proselyting, which he now stated explicitly and systematically.

Irreconcilably pugnacious toward his opponents, yet tenderly persuasive toward his followers, Nichiren almost always combined these two sides of his propaganda; but the writings produced within a few years after the first exile show, decidedly more than the earlier ones, a wonderful combination of the two. The delicate sentiment shown in his tender persuasions is now remarkably united with admonitions to honest faith and pure heart. The essay referred to above, written in the form of a catechism, is an example of this. After affirming the necessity of an exclusive devotion to the Lotus, it proceeds to emphasize the efficacy of simple-hearted faith:

“If you desire to attain Buddhahood immediately, lay down the banner of pride, cast away the club of resentment, and trust yourselves to the unique Truth. Fame and profit are nothing more than vanity of this life; pride and obstinacy are simply fetters to the coming life. … When you fall into an abyss and someone has lowered a rope to pull you out, should you hesitate to grasp the rope because you doubt the power of the helper? Has not Buddha declared, “I alone am the protector and savior”? There is the power! Is it not taught that faith is the only entrance (to salvation)? There is the rope! One who hesitates to seize it, and will not utter the Sacred Truth, will never be able to climb the precipice of Bodhi (Enlightenment). … Our hearts ache and our sleeves are wet (with tears), until we see face to face the tender figure of the One, who says to us, “I am thy Father.” At this thought our hearts beat, even as when we behold the brilliant clouds in the evening sky or the pale moonlight of the fast-falling night. … Should any season be passed without thinking of the compassionate promise, “Constantly I am thinking of you?” Should any month or day be spent without revering the teaching that there is none who cannot attain Buddhahood? Devote yourself whole-heartedly to the “Adoration to the Lotus of the Perfect Truth,” and utter it yourself as well as admonish others to do the same. Such is your task in this human life.

It must not be ignored, however, that even this writing contains a sharp argument against the opponents of the Lotus.

Another instance of tenderness is shown in a letter written to a lady who had asked about the rules to be observed during her monthly period. This was regarded by Japanese custom as a pollution, and women in this state were forbidden to approach Shinto sanctuaries. Her question, therefore, was, what she should do about the [Lotus Sutra] during that time. Nichiren deems it unnecessary to observe any precaution in that respect and admonishes her to recite the [Lotus Sutra] as usual. Yet he adds that, if, because of the habit and custom, she has scruples about doing so, she need not hold the rolls of the [Lotus Sutra] ; it will suffice to pronounce the Sacred Title. Delicate consideration and counsel of this kind are by no means rare in Nichiren’s instructions, but they become more frequent after his return from exile. In general, we see how and residence among the simple country folk had tempered Nichiren’s spirit, making him more gracious and sympathetic. His close contact with the people of Izu, especially the fisherman and his wife who sheltered him there, led him to give his instruction a more popular form and to take a deeper personal interest in his followers.

An Interlude and a Narrow Escape

His pugnacious spirit and his tender heart 46

His mother and his old master 47

The peril of the pine forest and the escape 49

His missionary journeys and converts 50