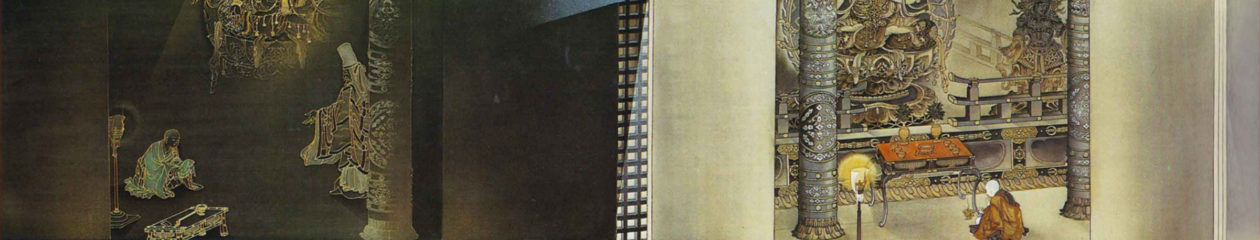

Day 29 covers all of Chapter 25, The Universal Gate of World-Voice-Perceiver Bodhisattva.

Having last month considered the many ways World-Voice-Perceiver helps those in trouble, we consider the merits earned by anyone who keeps the name of World-Voice-Perceiver Bodhisattva and bows and makes offerings to him even for a moment.

“Endless-Intent! Suppose a good man or woman keeps the names of six thousand and two hundred million Bodhisattvas, that is, of as many Bodhisattvas as there are sands in the River Ganges, and offers drink, food, clothing, bedding and medicine to them throughout his or her life. What do you think of this? Are his or her merits many or not?”

Endless-Intent said, “Very many. World-Honored One!”

The Buddha said:

“Anyone who keeps the name of World-Voice-Perceiver Bodhisattva and bows and makes offerings to him even for a moment, will be given as many merits as to be given to the good man or woman as previously stated. The merits will not be exhausted even after hundreds of thousands of billions of kalpas. Endless-Intent! Anyone who keeps the name of World-Voice-Perceiver Bodhisattva will be given these benefits of innumerable merits and virtues.”

See Avalokiteśvara