Continuing with my Office Lens houscleaning, I will be offering quotes from The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture for the next 10 days. Published by the University of Hawaii Press in 1989, this selection of essays was edited by George J. Tanabe Jr. and Willa Jane Tanabe. The Tanabes are famous – perhaps infamous – for the editors’ Introduction, in which they describe the Lotus Sutra as a text “about a discourse that is never delivered, a lengthy preface without a book.”

Continuing with my Office Lens houscleaning, I will be offering quotes from The Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture for the next 10 days. Published by the University of Hawaii Press in 1989, this selection of essays was edited by George J. Tanabe Jr. and Willa Jane Tanabe. The Tanabes are famous – perhaps infamous – for the editors’ Introduction, in which they describe the Lotus Sutra as a text “about a discourse that is never delivered, a lengthy preface without a book.”

Having been introduced to the book as a footnote for that quote I was not surprised to find this infamous Introduction stumbles in summarizing the sutra.

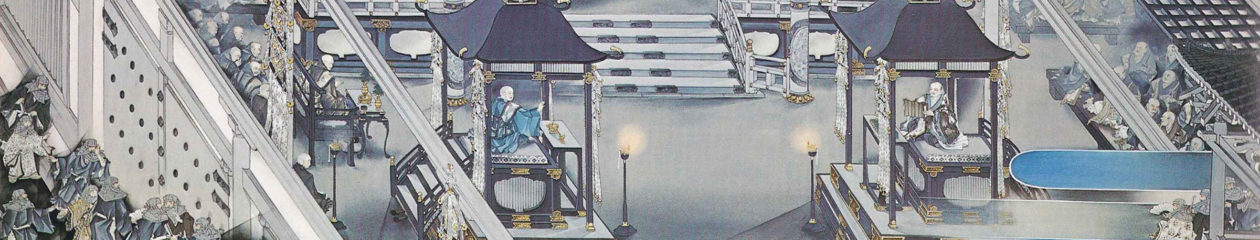

Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture, {author-numb}In the opening scene of the Lotus Sutra, great sages, deities, and kings gather by the tens of thousands to hear the Buddha speak. After the multitude showers him with reverent offerings, the Buddha offers some preliminary words and then enters a state of deep concentration. The heavens rain flowers and the earth trembles while the crowd waits for the sermon. Then the Buddha emits a glowing light from the tuft of white hair between his brows and illuminates the thousands of worlds in all directions of the universe. The bodhisattva Maitreya, wanting to know the meaning of this sign, asks Mañjuśrī, who searches back into his memory and recalls a similar display of light:

You good men, once before, in the presence of past Buddhas, I saw this portent: when the Buddhas had emitted this light, straightway they preached the great Dharma. Thus it should be understood that the present Buddha’s display of light is also of this sort. It is because he wishes all the living beings to be able to hear and know the Dharma, difficult of belief for all the worlds, that he displays this portent.

Everything that is happening now, recalls Maitreya, happened in that distant past when the Buddha preached the Sutra of Innumerable Meanings and entered samādhi as the universe trembled and rained flowers.

Okay. It’s just a typo. It’s not like I haven’t made any typos here. I’m sure the editors know that it is Mañjuśrī who recalls his past life experience.

As for that infamous quote, here’s the context:

Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture, {author-numb}The status of the sutra is raised to that of an object of worship, for it is to be revered in and of itself because of the merits it asserts for itself. As praises for the Lotus Sutra mount with increasing elaboration, it is easy to fall in with the sutra’s protagonists and, like them, fail to notice that the preaching of the Lotus sermon promised in the first chapter never takes place. The text, so full of merit, is about a discourse which is never delivered; it is a lengthy preface without a book.

The Lotus Sutra is thus unique among texts. It is not merely subject to various interpretations, as all texts are, but is open or empty at its very center. It is a surrounding text, pure context, which invites not only interpretation of what is said but filling in of what is not said. It therefore lends itself more easily than do other scriptures to being shaped by users of the text.

The fact that the preaching remains an unfulfilled promise is never mentioned, mostly because that fact is hardly noticed, or because the paean about the sermon sounds like the sermon itself. The text is taken at face value: praise about the Lotus Sutra becomes the Lotus Sutra, and since the unpreached sermon leaves the text undefined in terms of a fixed doctrinal value (save, of course, the value of the paean) it can be exchanged at any number of rates. Exchange involves transformation, the turning of one thing into another, and the Lotus Sutra can thus be minted into other expressions of worth. That transformation process, beginning with the original text itself, did in fact take place, and the different ways in which the Lotus Sutra was transformed into aspects of Japanese culture are the subject of this collection of essays.

I will offer quotes from two of the 10 essays. Some of the essays are not quotable and some I find objectionable. Here’s an example of the latter from the essay “The Meaning of the Formation and Structure of the Lotus Sutra” by Shioiri Ryōdō:

Lotus Sutra in Japanese Culture, {author-numb}In the mid-Heian period the Pure Land belief centered on Amida became quite popular, and in Nihon ōjō gokuraku ki (An Account of Japanese Reborn in Paradise) by Yoshishige no Yasutane (934-997) there are many legends patterned after examples of the Chinese Buddhists considered to have been reborn in the Pure Land paradise. Eshin Sōzu (Genshin, 942-1017), a priest of Mt. Hiei, is famous for writing Ōjōyōshū (Essentials for Rebirth), in which he describes paradise and hell in detail and speaks of loathing the defilements of this world and desiring rebirth in paradise. In a certain sense it could be said that he perfected the Pure Land teaching on Mt. Hiei. Those who gathered around these two men heard lectures on the Lotus Sutra, wrote poems based on phrases from the sutra, and made the recitation of the nembutsu their central practice. Recitations of the Lotus Sutra and the name of Amida coexisted without the slightest contradiction. When I was asked by Professor Inoue Mitsusada to annotate the Ōjōden (Biographies of Rebirth) and the Hokke genki (Miraculous Tales of the Lotus Sutra) for the Iwanami series on Japanese thought, I spent nearly a year at this task and was keenly aware of the compatibility of the two practices as I became intimate with the biographies of those reborn. The Ōjōden is a collection of biographies of forty-five Buddhists, beginning with Shōtoku Taishi; of the thirty-five who are said to have gained rebirth in paradise, seven are explicitly described as believers in the Lotus Sutra. The number can be extended to ten if we include those who I think were believers or practitioners of the Lotus Sutra even though there is no explicit reference to this. In a text where only three people are said to have practiced esoteric Buddhism apart from their Pure Land belief and only two were adherents of other sutras, we can see the extent to which the Lotus Sutra was preferred.

Yes, in the Heian period the “recitations of the Lotus Sutra and the name of Amida coexisted without the slightest contradiction.” That’s exactly why Nichiren Shōnin was so adamant that things had gotten out of hand.

While I did not quote from Geroge Tanabe’s “Tanaka Chigaku: The Lotus Sutra and the Body Politic,” I recommend it as an introduction to Tanaka and his fervent nationalist Nichirenism.