In reply to the question of the bodhisattva Infinite Thought, “How is it that the Bodhisattva Regarder of the Cries of the World wanders in this sahā-world?” the Buddha (in the Chinese translation) sets forth the thirty-three transformations of that bodhisattva. (The Sanskrit text gives sixteen, and the correspondence is shown in parentheses.) These comprise the three kinds of holy body, the six types of heavenly body, the five types of human body, the bodies of the four groups, the four female bodies, the youth, the dragon, the eight kinds of nonhuman body, and the diamond-holding god.

- The buddha body (Sanskrit text no. 1, buddha-rūpa)

According to the Karuṇāpuṇdārika-sūtra (Pei-hua Ching, T. 157), when the buddha Amitāyus enters nirvana and the True Law declines and disappears, the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara will become the buddha Samantaraśmyuddhrtaśrikūṭarāja; according to the Kuan-shih-yin p’u-sa shou-chi Ching (T. 371, Māyopamasamādhi-sūtra), he will become Samantaraśmiśrikūṭarāja Buddha. Worthy of note too is that in the Larger Sukhāvativyūha-sūtra, Amita’s teacher when he was the monk Dharmākara was Lokeśvara Buddha, a name somewhat similar to Avalokiteśvara. (Sanskrit text no. 2, bodhisattva-rūpa) - The pratyekabuddha body (Sanskrit text no. 3, pratyekabuddha-rūpa). The solitary buddha who practices in the depths of forests and mountains.

- The śrāvaka body (Sanskrit text no. 4, śrāvaka-rūpa)

The Theravādin practitioner training as a monk in a monastery. - The Brahmā body (Sanskrit text no. 5, brahma-rūpa)

The king of the Brahmā Heaven, also called the Brahmā King. Brahmā forms, with Viṣṇu and Śiva, the Hindu “trinity.” This is a deified form of the impersonal principle Brahman, which developed in the Upaniṣads. He was once considered the principal deity, but he lacked specificity and he was overshadowed by the other two deities. - The Indra body (Sanskrit text no. 6, Śakra-rūpa)

Also called Śakro devānāṃ Indraḥ. In the Ṛg Veda he had the character of a weather deity who sent rain and storms. He was gradually personified, and is drawn as a deity of military prowess and a hero deity. As a Buddhist deity, Indra defends Buddhism against its enemies and is magnanimous toward those who take refuge in it. His blessings are the subject of praise. - The Īśvara body (Sanskrit text no. 9, Īśvara-rūpa)

In the early Vedas, Īśvara (“lord of the universe”) represents the authority of the lord; in the Atharva-Veda, Īśvara means the power of the deity and the cosmic Purūṣa (the eternal person); and in the Mahābhārata and later writings it is used to mean the supreme deity. With the development of Avatāra thought, Īśvara, in common with such deities as Krishna, Vāsudeva, and Rāmachandra, as well as the historical Buddha, came to be considered an incarnation of Viṣṇu, the lord of all existence, and was absorbed into the concept of Viṣṇu. Viṣṇu exhibits a warm and human face. His heaven is higher than the Brahmā heavens, he emits an eternal light, he has four arms and lotus eyes, he wears a yellow robe, he rides an eight-wheeled golden vehicle, his banner depicts Garuda, and his weapons are a cakravartin’s wheel, a conch shell, a club, and a bow. He has many names; he is considered a yoga practitioner, but appears in this world through incarnations to punish evil-doers and to save the good. The number of his incarnations grew as time went by. He is beloved by the people as the god abounding in blessings. - The Maheśvara body (Sanskrit text no. 10, Maheśvara-rūpa)

Maheśvara (“the great god”) is another name for Śiva. He is said to have been born from Brahmā, or alternatively, out of Viṣṇu’s forehead. He has four faces. With his eastern face he governs all things; with his northern face he sports with his spouse Umā; with his western face he delights living beings; and with his southern face he is the destroyer. He has three eyes (the sun, the moon, fire) and carries as weapons a spear, a bow, a battle-ax, and a trident. He has many names, relating to either his ferocious or his benevolent aspect. He is the creator Paśupati, the Lord of the Animals, in the form of a yoga practitioner. Besides being a true yogin, he also loves music and dancing. Śiva appears to have developed from the Vedic god Rudra, the deity of storms or fire, but his origins are uncertain. He may have been a forest god whose disease-bearing arrows assail human beings. He is also connected with lingam worship as a fertility deity. A figure identified with his earliest form has been discovered in the pre-Aryan ruins of the Indus Valley, but it is not clear whether Śiva originated in indigenous beliefs. - The body of a general (Sanskrit text no. 11, Cakravartirāja-rūpa)

“Cakravartirāja,” the “wheel-rolling king,” was used in post-Vedic writings to refer to a person who governed territory (“wheel”); an example of its allegorical use appears in the Mahabharata. “Wheel” means the chariot of the ruler which moves around the land; “rolling” means unobstructed movement. The territory of a “wheel-rolling” king extends, like Aśoka’s, from sea to sea. - The Vaiśravaṇa body (Sanskrit text no. 13, Vaiśravaṇa-rūpa)

Vaiśravaṇa is also called Kubera. He is one of the four guardian gods, protecting the northern direction, Jambudvipa, and dwelling on the northern side of Mount Sumeru. He possesses vast wealth and defends Buddhism. - The body of a king (Sanskrit text no. 14, senāpati-rūpa)

- The body of a rich man

The rich man is also known as a merchant (śreṣṭhin), and is a leader of a guild of bankers or merchants. Originally the term meant an excellent or a superior man, but in the Brāhmaṇas it meant the leader of a village community. With urban development, the term was used for the heads of the influential merchant class. - The body of a householder

In the Vedas and the Brāhmaṇas, the householder (gṛhapati) was the one who performed the sacrifices. With the expansion of the economy, those who acquired wealth through commerce, handicrafts, and farming were the recipients of respect despite the social class of their birth and gṛhapati came to mean the heads of the extended patrilineal family. They were influential members of the new class of proprietors; though they had the responsibility of maintaining their own households and were also bound by the law of inheritance of their kinship groups, still they could freely dispose of the wealth they had acquired outside the regulation of their tribes. This newly arisen class, especially the gṛhapati representative of the commercial and manufacturing class in urban centers, later gave financial support to the new religions of Jainism and Buddhism. - The body of an official

Officials performing the functions of a state’s government under the monarch were called Mahāmātra. Under Aśoka, for instance, there were supervisors of the Dhamma, accountants, tax-collectors, and superintendents of border areas. - The body of a Brahman (Sanskrit text no. 15, Brāhmaṇa-rüpa)

The Brahman, who functioned as a priest, occupied the top of the caste system in Brahmanical society. He performed the rituals of Brahmanism. - The body of a bhikṣu

The bhikṣus were religious practitioners belonging to new, anti-Brahmanical sects who had left their homes to lead a life of mendicancy. In Buddhism the term was used to refer to male monks aged more than twenty, members of the bhikṣu-saṃgha. - The body of a bhikṣuṇī

The bhikṣuṇī was a female religious practitioner aged over twenty, a member of the bhikṣuṇī-saṃgha. - The body of an upāsakā

The upāsakā was a male lay believer. - The body of an upāsikā

The upāsikā was a female lay believer. The above four items represent the four groups, the basic constituents of the Buddhist Saṃgha. - The body of a wealthy woman

- The body of the wife of a householder

- The body of the wife of an official

- The body of the wife of a Brāhman

- The body of a boy

- The body of a girl

- The body of a deity

Deities refer to heavenly existence. The Ṛg Veda generally refers to thirty-three deities, eleven of each occupying the heavens, the sky, and the earth respectively. These gods were personalizations of natural phenomena and component forces, and of pivotal experiences and ideas, and gods of the sun, the dawn, thunder, storms, rain, wind, water, and fire, among others, received songs of praise. However, in the process of the transmutation from Brahmanism to Hinduism, there was a change in the idea of divinity. The Vedic gods fell from their superior position and lost their power. This phenomenon is particularly striking in the Mahābhārata (second century BCE to second century CE). Here the character of the gods changes; all are now immortal, able to move freely through the air, dwell in the heavenly realm, and from there descend as they wish to the world below. - The body of a nāga

The nāga is a snake, particularly the cobra. In Indian mythology it appears as half man, half snake. Certain tribes in Assam and northern Burma still bear the name Nāga. In Gandhāra and Kashmir, a nāga cult existed from earliest times among the aboriginal, lower-caste inhabitants; these converted later to Buddhism when it was brought to the area. In this cult, nāgas are believed to dwell in bodies of water, call the clouds to them, and bring the rain. Traces of the nāga cult are to be found in the stupas of Sāñcī, Amaravatī, and Bhārhut. - The body of a yakṣa (Sanskrit text no. 8, yakṣa-rūpa)

Yakṣas are mythological demigods who inhabit moorlands and forests. Their cult goes back to the Vedic age, when they were vegetation gods of the village communities; they were ignored, though, by the Brahmans. Evidence of the currency of the cult can be found in Jain myths and on the stupas of Sāñcī, Amaravatī, and Bhārhut. In most villages the yakṣa lived in the sacred tree, protecting the village from harm and ensuring its prosperity. Stories in the Purānas, legends of the gods, that use yakṣa mythology are part of the legend of Kubera, the god of treasure and wealth. In the Bhārhut carvings, small animals stand above the yakṣas. Yakṣas can assume many shapes, including the female form, and their activities are unlimited. - The body of a gandharva (Sanskrit text no. 7, gandharva-rūpa)

In the Ṛg Veda, Gandharva was the deity who guarded the celestial and divine herb, soma. In the Mahābhārata, the gandharvas were singers and musicians for the gods. According to popular Buddhist lore, they attended the deities dwelling in the realm of the four heavenly kings. In both Buddhism and Hinduism, they were called gandharvas because they “ate perfume.” - The body of an asura

Asura (god, divine) is of the same origin as deva; in the Ṛg Veda it designates a particular god, said to be the equivalent of the supreme deity of Zoroastrianism, Ahura Mazda, and means “life force” or “energy.” Later deva and asura became personified and stood for opposite forces: whereas the devas were kindly, the asuras were fearful, possessing magical powers and hard to approach, representing the demonic qualities. As Indra represents the devas, Varuṇa, the master of ritual, represents the asuras. - The body of a garuda

The garuda is half man, half bird, with the beak and claws of a flesh-eating bird, and the torso of a human being. In the Mahābhārata and the Puraṇas the garuda is the subject of many tales. It is compared to the sun’s rays, which burn everything; it is a destroyer that intimidates and eats snakes. Popular belief says that the garuda has the power to cure all suffering stemming from a snakebite. Many of the garuda tales appear to be based on ancient non-Aryan sources, and their meaning is unclear. - The body of a kiṃnara

The kiṃnara is a deity of a primitive folk cult; it has a human body and a horse’s head, or alternatively a horse’s body and a human head. It occupied an important place among post-Vedic cult deities, but later became relegated to an inferior position. The kiṃnaras became heavenly musicians, together with the gandharvas in the paradise of Kubera. - The body of a mahoraga

The mahoraga is the deification of the python, which slithers along on its stomach. Coveting wine and meat, it degenerated into a demonic force. It is said that insects devour its body from inside. In the form of a human body and a snake’s head, it is a heavenly musician. - The body of Vajrapāni (Sanskrit text no. 16 Vajrapāni-rūpa)

“Vajrapāni” means one who holds a hammer, the “diamond pounder.” He is also called the Vajra wrestler. He has appeared in Buddhist writings since the early period, as an attendant upon Śākyamuni. He protects Buddhism from its slanderers and destroys them with his hammer.

(Numbers 25 to 32 above are known as the eight kinds of deities that protect Buddhism.)

(Sanskrit text no. 12 piśāca-rūpa)

Piśācas are said to be flesh- and blood-eating demons, variously described as being created by Brahmā; by Krodhā, a female demon personifying wrath; or by darkness. Like yakṣas, they either dwell or congregate at funeral pyres and at night go out to deserted houses, roads, and doorways. It is believed that any who see them will die within nine months.

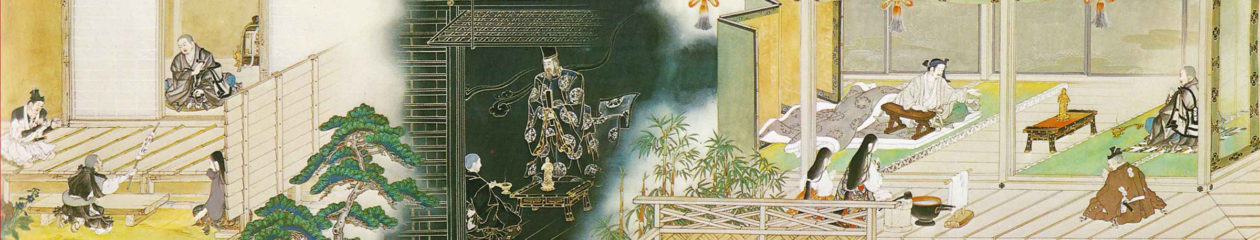

I have briefly sketched the thirty-three forms of Avalokiteśvara as they appear in Kumārajīva’s translation of the Lotus Sutra, and the sixteen forms that appear in the Sanskrit text, as well as in Dharmarakṣa’s translation, and the Tibetan translation, in terms of their incidence in religious history. There is a view that the Kumārajīva translation systematized the various forms, indicating that Avalokiteśvara assumes different incarnations and forms in response to circumstances in order to be able to approach the various beings to teach them the Law and bring them to deliverance.

Source elements of the Lotus Sutra, p 366-373